Get up and running

Different ways to run RStudio

We can run RStudio in a variety of different ways—

- Most people use the version of RStudio called RStudio Desktop, either in its free-to-use guise (Open Source Edition) or the commercial version (RStudio Desktop Pro). The desktop version of RStudio are stand-alone applications that run locally on a computer and have to be installed like any other piece of software. This is generally easy, but you can run into problems if you have an old computer or a Chromebook.

- The second way to use RStudio is by accessing a version called RStudio Server through a web browser. RStudio Server is usually administered by professional IT people. Life is easy if you belong to an organisation that has set up RStudio Server, because all you need to get going is a user account, a semi-modern web browser and an internet connection.

- Finally, the company that makes RStudio also runs a commercial cloud-based solution called RStudio Cloud. This allows anyone web browser and an internet connection to use R and RStudio. Although there is a free version, this is fairly limited meaning you end up paying a monthly fee to do ‘real work’. However, RStudio Cloud can be a good backup option when all else fails.

Do you need to install R and RStudio?

If you’re lucky enough to have access to RStudio Server or an RStudio Cloud account you don’t need to install R and RStudio on your own computer. Just access those cloud service through a decent web browser. That said, it can be useful to have a local copy on your own computer, e.g. because you don’t have a reliable internet connection. Obviously, if you can’t access those cloud services you’ll have to install R and RStudio to use them!

Installing R and RStudio locally

It does not need to cost a penny to use R and RStudio. The source code for R is open source, meaning anyone with the time, energy and expertise is free to download it and alter it as they please. Open source does not necessarily mean free, as in it costs £0 to use, but luckily R is free in this sense. On the other hand, RStudio is developed and maintained by a for-profit company (called… RStudio). Luckily, because they make their money selling professional software and services, the open source desktop version of RStudio is also free to use. This section will show you how to download and install R and RStudio.

Installing R

In order to install R you need to download the appropriate installer from the Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). We are going to use the “base distribution” as this contains everything you need to use R under normal circumstances. There is a single installer for Windows. On a Mac, it’s important to match the installer to the version of OS X. In either case, R uses a the standard install mechanism that should be familiar to anyone who has installed an application on their machine. There is no need to change the default settings—doing so will probably lead to problems later on.

After installing R it should be visible in the Programs menu on a Windows computer or in the Applications folder on a Mac. In fact, that thing labelled ‘R’ is very simple a Graphical User Interface (GUI) for R. When we launch the R GUI we’re presented with something called the Console, which is where we can interact directly with R by typing things at the so-called prompt, >, and a few buttons and menus for managing common tasks. We will not study the GUIs in any detail because we recommend using RStudio, but it’s important to be aware they exist so that you don’t accidentally use them instead of RStudio.

Installing RStudio

RStudio can be downloaded from the RStudio download page. The one to go for is the Open Source Edition of RStudio Desktop, not the commercial version of RStudio Desktop called RStudio Desktop Pro. RStudio installs like any other piece of software—just run the installer and follow the instructions. There’s no need to configure after after installation.

A quick look at RStudio

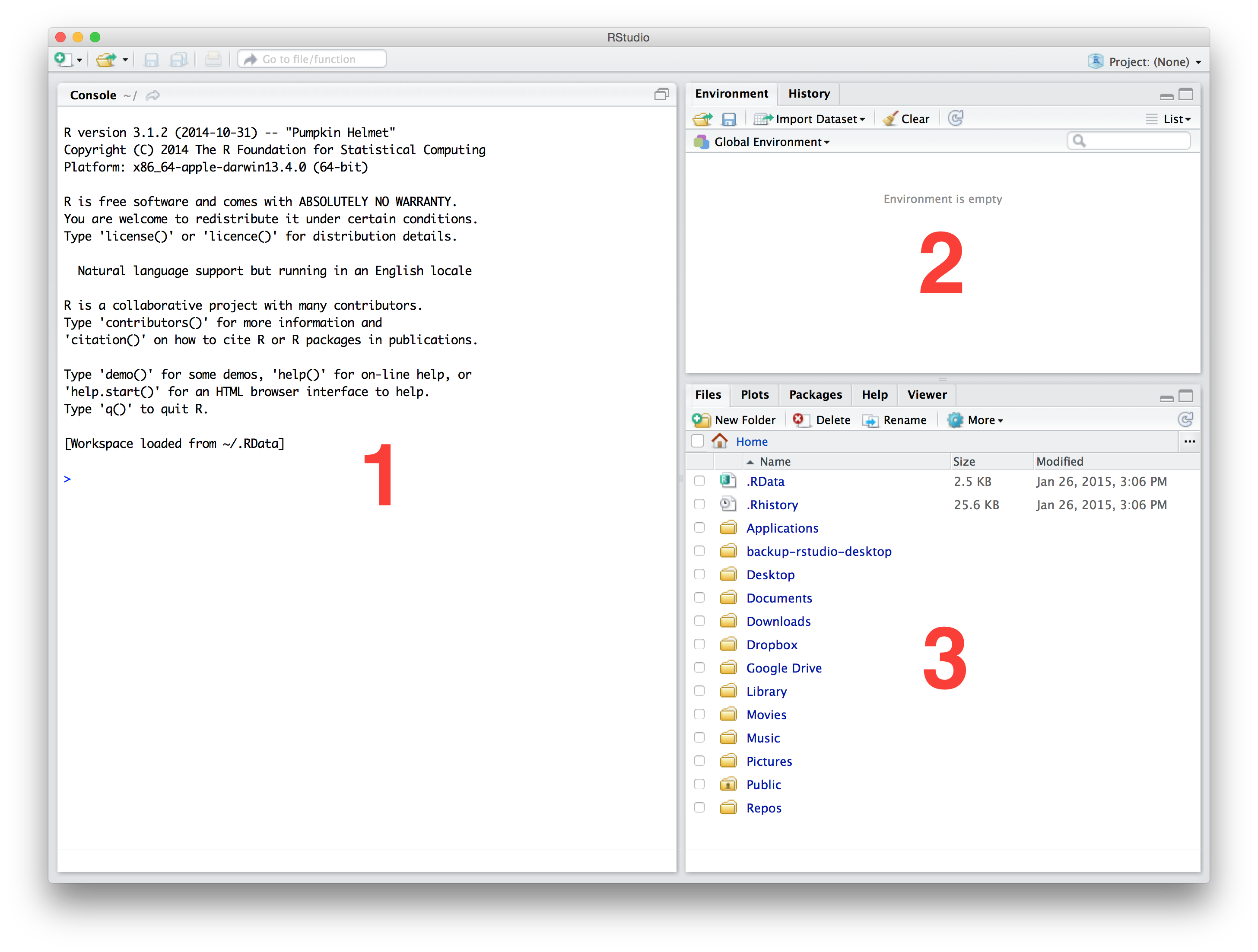

Once installed RStudio runs like any other stand-alone application via the Programs menu or the Applications folder on a Windows PC or Mac, respectively (though it will only work properly if R is also installed). Here is how RStudio appears the first time it runs on a Mac:

There are three panes inside a single window, which we have labelled with red numbers. Each of these has a well-defined purpose. Let’s take a quick look at these:

The large window on the left is the Console. This is basically where R lives inside RStudio. The Console lets you know what R is doing and provides a mechanism to interact with R by typing instructions. All this happens at the prompt,

>. You will be working in the Console in the next chapter so we won’t say any more about this here.The window at the top right contains two or more tabs. One of these, labelled Environment, allows us to see all the R ‘objects’ we can currently access. Another, labelled History, allows us to see a list of instructions we’ve previously sent to R. The buttons in this tab allow us to reuse or save these instructions.

The window at the bottom right contains five tabs. The first, labelled Files, gives us a way to interact with the files and folders. The next tab, labelled Plots, is where any figures we produce are displayed. This tab also allows you to save your figures to file. The Packages tab is where we view, install and update packages used to extend the functionality of R. The Help tab is where you can access and display various different help pages. Finally, Viewer is an embedded web browser.

My RStudio looks different!

Don’t be alarmed if RStudio looks different on your computer. RStudio saves its state between different sessions, so if you’ve have already messed about with it you will see these changes when you restart it. For example, there is a fourth pane that is often be visible in RStudio—the source code Editor we mentioned above.

Working at the Console in RStudio

R was designed to be used interactively—it is what is known as an interpreted language, which we can interact with via something called a Command Line Interface (CLI). This is just a fancy way of saying that we can type instructions to “do something” into the Console and those instructions will then be interpreted when we hit the Enter key. If our R instructions do not contain any errors, R will then do something like read in some data, perform a calculation, make a figure, and so on. What actually happens obviously depends on what we ask it to do.

Let’s briefly see what all this means by doing something very simple with R. Type 1 + 3 at the Console and hit the Enter key:

1+3## [1] 4The first line above just reminds us what we typed into the Console. The line after that beginning with ## shows us what R printed to the Console after reading and evaluating our instructions.

What just happened? We can ignore the [1] bit for now (the meaning of this will become clear later in the course). What are we left with – the number 4. The instruction we gave R was in effect “evaluate the expression 1 + 3”. R read this in, decided it was a valid R expression, evaluated the expression, and then printed the result to the Console for us. Unsurprisingly, the expression 1 + 3 is a request to add the numbers 1 and 3, and so R prints the number 4 to the Console.

OK… that was not very exciting. In the next chapter we will start learning to use R to carry out more useful calculations. The important take-away from this is that this sequence of events—reading instructions, evaluating those instructions and printing their output (if there is any output)—happens every time we type or paste something into the Console and hit Enter.

What does that word ‘expression’ mean?

Why do we keep using that word expression? Here is what the Wikipedia page says:

An expression in a programming language is a combination of explicit values, constants, variables, operators, and functions that are interpreted according to the particular rules of precedence and of association for a particular programming language, which computes and then produces another value.

That probably doesn’t make much sense! In simple terms, an R expression is a small set of instructions that tell R to do something. That’s it. We could write ‘instructions’ instead of ‘expressions’ throughout this book but we may as well use the correct word.