Introductory Biostatistics with R

2022-12-07

Overview

This book provides a self-contained introduction to the analysis of biological data using the R programming language. Topics include principles of experimental design principles of frequentist statistics, simple statistical tests, analysis of variance, regression, analysis of categorical data, and non-parametric statistics.

Why do a data analysis course?

To do science yourself, or to understand the science other people do, you need to understand the principles of experimental design, data collection, statistical analysis and scientific presentation. That does not mean becoming a maths wizard or a computer genius. It means knowing how to make sensible decisions about designing studies and collecting data and then interpreting those data correctly. Sometimes the methods required are straightforward, sometimes more complex. You aren’t expected to get to grips with all of them, but what we hope to do in the course is to give you a good practical grasp of the core techniques that are widely used in biology. You should then be equipped to use these techniques intelligently and, equally importantly, know when they are inappropriate and when you need to seek help to find the correct way to design or analyse your study.

With some work on your part, you should acquire a set of skills that you can apply in practicals, field courses, and project work. These same skills will almost certainly also be useful in other situations, whether doing biology, or something completely different. We live in a world increasingly flooded with data, and people who know how to make sense of this are in high demand.

Programming prerequisites

This book assumes you have used R and RStudio before and that you are comfortable with the material given in the associated Exploratory Data Analysis with R book. What follows is a quick summary of what you need to know.

R and RStudio

R is a programming language designed first and foremost to support data analysis. We use it to carry out all the statistical analyses covered in this book. R is a fully-fledged programming language, meaning that we have to interact with it by writing computer code. Essentially, R sits and waits for instructions in the form of text (R code). A user can type in those instructions, or they can be sent to it from another helper program. This book assumes you have written R code before and know how to ‘run it’ via these two routes.

We strongly recommend that you use a helper program when working with R. We like RStudio. RStudio makes R a more pleasant and productive tool. RStudio provides a Source Code Editor for working with R code. It also provides a visual, point-and-click means of accessing various language-specific features, such as install packages (see below).

Using packages

R packages extend the basic functionality of R so that we can do more with it. They bundle together R code, data, and documentation in a standardised way that makes it easy to use and share with others. This book uses a subset of the tidyverse ecosystem of packages:

- The readr package for reading data into R

- The dplyr package for data manipulation

- The ggplot2 package for making plots

You need to understand R’s package system to use these. This means knowing that installing a package and loading the package are different operations. We only have to install a package onto our computer once, but we have to load the package every time we want to use it in a new R session. If that is confusing, revise the package system chapter Exploratory Data Analysis with R book.

Installing a package can be done via the install.packages function, e.g. use this code to install the dplyr package:

install.packages("dplyr")Alternatively, use the simple RStudio menu interface to install packages. This is accessed via the Install button in the packages tab of the lower right window in RStudio. Loading and attaching a package so that it can be used in a given session happens via the library function, e.g.

library("dplyr")What goes in your script?

We should not routinely leave install.packages lines in our scripts. Why? Because we don’t usually need to install a package every time we run a script—installing packages is a slow ‘do once’ operation. We do usually place one or more library lines at the start of a script to ensure the required packages available in the current R session every time we run the script.

Working with data

All the examples use data sets that are stored in CSV files. You can get these by emailing the lead author. We assume you know how to use a function like read_csv from the readr package to get those data into R. Remember, when using read_csv we end up with a ‘tibble’: the tidyverse version of a data frame. You could also use the base R read_csv function to read CSV data into a standard base R data frame—the differences don’t matter in this book.

Tibbles and data frame are a table-like objects with rows and columns. They collect together different variables, storing each of them as a named column. We always assume that the data inside these objects are organised according to tidy data conventions. Tidy data has a specific structure that makes it easy to manipulate, model and visualise. A tidy data set is one where each variable is only found in one column, and each row contains one unique observation.

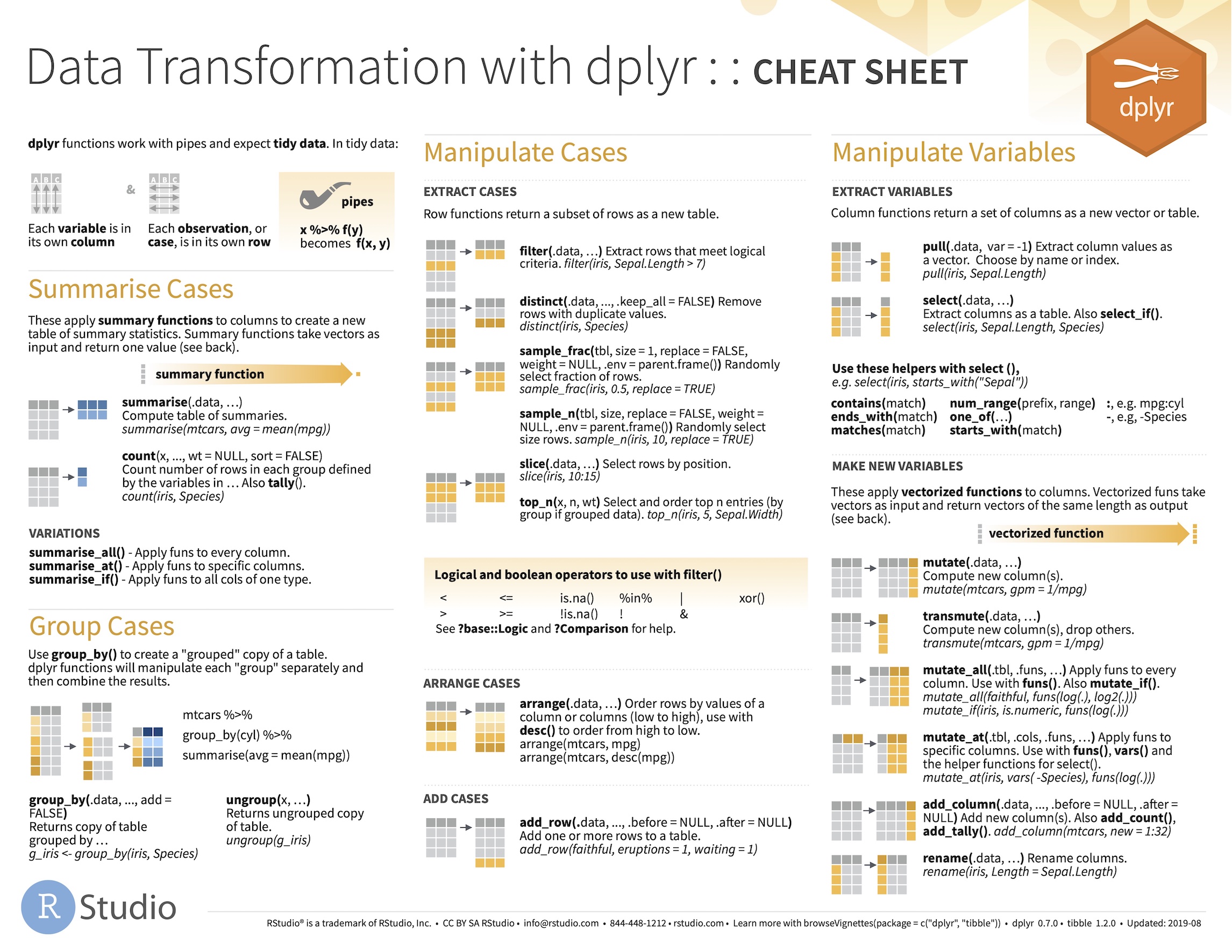

Data wrangling with dplyr

We assume you know how to manipulate data frames and tibbles using the dplyr package. The dplyr package makes it easy to manipulate ‘rectangular data’ that lives in tibbles and data frames. dplyr is orientated around a few core functions, each designed to do one thing well. These dplyr functions are sometimes referred to as its ‘verbs’ to reflect the fact that they ‘do something’ to data. For example:

selectobtains a subset of variables,mutateconstructs new variables,filterobtains a subset of rows,arrangereorders rows, andsummarisecalculates information about groups.

Notice that the names are chosen to reflect what each function does to the input data. We’ll routinely use these—along with a few additional functions such as rename and group_by—to create new variables, subset data based on some criteria, and calculate summaries for different subsets of data.

Plotting with ggplot2

We assume you know how to create data visualisations using the ggplot2 package. A visualisation is created by defining one or more layers, where each layer is associated with some data and a set of rules for how to display the data. We assume you know how to use the ggplot2 ‘grammar’ to set up:

- one or more layers,

- a set of scales,

- a coordinate system, and

- a facet specification for multi-panel plots (optional).

We assume you know how to make basic plots to aid exploratory data analysis. You should be able to:

- visualise single-variable distributions using dot plots and histograms (numeric variables) and bar plots (categorical variables);

- visualise associations between pairs of variables using scatter plots (numeric vs numeric), bar plots (categorical vs categorical), and box plots (numeric vs categorical).

We also assume you know how to make more informative plots by defining additional aesthetic mappings (e.g. colour and fill), or using faceting to construct a multi-panel plot according to the values of categorical variables.

A dplyr cheat sheet

The developers of RStudio have produced very usable cheat sheats that summarise the core packages in the tidyverse ecosystem.

Download these, print out a copy, and refer to it when you need to do something with dplyr or ggplot2.

How the book is formatted

We have adopted several formatting conventions in this book to distinguish between normal text, R code, file names, and so on. You need to be aware to make best use of the book.

Text, instructions, and explanations

Normal text—instructions, explanations and so on—are written in the same type as this document. We will tend to use bold for emphasis and italics to highlight specific technical terms when they are first introduced. In addition:

This typefaceis used to distinguish R code within a sentence of text: e.g. “We use themutatefunction to change or add new variables.”- A sequence of selections from an RStudio menu is indicated as follows: e.g. File ▶ New File ▶ R Script

- File names referred to in the general text are given in upper case in the normal typeface: e.g. MYFILE.CSV.

At various points, you will come across text in different coloured boxes. These are designed to highlight stand-alone exercises or little pieces of supplementary information that might otherwise break the flow. There are three different kinds of boxes:

Action!

This is an action box. We use these when we want you to do something. Do not ignore these boxes.

R code and output

We try to illustrate ideas using snippets of real R code where possible. Stand alone snippets are formatted like this:

tmp <- 1

print(tmp)## [1] 1The lines that start with ## show us what R prints to the screen after it evaluates some R code; they show the output. The lines that do not start with ## show us the R code; they show us the input. So remember, the absence of ## shows us what we are asking R to do. Otherwise, we are looking at something R prints in response to these instructions.