Chapter 15 One-way ANOVA in R

Our goal in this chapter is to learn how to work with one-way ANOVA models in R. As we did with regression, we’ll do this by working through an example. We’ll start with the problem and the data, then work through model fitting, significance testing, and finally, present the results.

15.1 Introduction

We will use the corncrake example from the last chapter to demonstrate how to conduct a one-way ANOVA in R. Recall that these data show the results of an experiment comparing the weight gain of eight corncrake hatchlings on each of four supplements and one control diet.

The data live in the ‘CORN_CRAKE.CSV’ file. The code below assumes those data have been read into a tibble called corn_crake. Set that up if you plan to work along.

15.1.1 First steps

What lives inside the corn_crake data set? There are no surprises:

## Rows: 40

## Columns: 2

## $ Supplement <chr> "None", "None", "None", "None", "None", "None", "None", "No…

## $ WeightGain <dbl> 13, 20, 17, 16, 15, 14, 10, 20, 15, 18, 10, 22, 23, 19, 25,…There are 40 observations in the data set and 2 variables (columns), called Supplement and WeightGain.

15.2 Model fitting and significance tests

Carrying out ANOVA in R is quite simple, but as with regression, there is more than one step.

The first involves a process known as fitting the model (or just model fitting). This is the step where R calculates the relevant means and the additional information needed to generate the results in step two. We call this step model fitting because an ANOVA is a type of model for our data: it is a model that allows the mean of a variable to vary among groups.

How do we fit an ANOVA model in R? We use the lm function again. Remember what the letters ‘lm’ stand for? They stand for ‘(general) linear model’. An ANOVA model is just another special case of that general linear model. Here is how we fit a one-way ANOVA in R, using the corncrake data:

By now, this kind of thing is probably starting to look familiar. We have to assign two arguments:

The first argument is a formula. We know this because it includes a ‘tilde’ symbol:

~. The variable name on the left of the~must be the numeric response variable whose means we want to compare among groups. The variable on the right should be the indicator (or predictor) variable that says which group each observation belongs to. These areWeightGainandSupplement, respectively.The second argument is the name of the data frame that contains the two variables listed in the formula.

How does R know which model to use?

How does R know we want to use an ANOVA model? After all, we didn’t specify this anywhere. The answer is that R looks at what type of vector Supplement is. It is a categorical character vector, and so R carries out an ANOVA. It would do the same if Supplement had been a factor. However, if the values of Supplement had been stored as numbers then R would not have fitted an ANOVA. Instead, it would have assumed we meant to fit a regression model, which is seldom appropriate. This is why we never store categorical variables as numbers in R.

Avoid using numbers to encode the values of a categorical variable if you want to avoid making mistakes when fitting models!

Notice that we did not print the results to the console. Instead, we assigned the result a name —corncrake_model now refers to a model object. What happens if we print this to the console?

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = WeightGain ~ Supplement, data = corn_crake)

##

## Coefficients:

## (Intercept) SupplementEarlybird SupplementLinseed

## 14.250 8.625 4.250

## SupplementNone SupplementSizefast

## 1.375 4.750Not a great deal. Printing a fitted model object to the console is not very useful when working with ANOVA. We just see a summary of the model we fitted and some information about the model coefficients. Yes, an ANOVA model has coefficients, just like a regression does.

Assumptions

The one-way ANOVA model has a series of assumptions about how the data are generated. This point in the workflow would be a good place to evaluate whether or not these may have been violated. However, we’re going to tackle this later in the Assumptions and Diagnostics chapters. For now, it is enough to be aware that there are assumptions associated with one-way ANOVA and that you should evaluate these when working with your own data.

15.2.1 Interpreting the results

We really want a p-value to help us determine whether there is statistical support for a difference among the group means. That is, we need to calculate things like degrees of freedom, sums of squares, mean squares, and the F-ratio. This is step 2.

We use the anova function to do this:

## Analysis of Variance Table

##

## Response: WeightGain

## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

## Supplement 4 357.65 89.413 5.1281 0.002331 **

## Residuals 35 610.25 17.436

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1Notice that all we did was pass the anova function one argument: the name of the fitted model object. Let’s step through the output to see what it means. The first line just informs us that we are looking at an ANOVA table, i.e. a table of statistical results from an analysis of variance. The second line just reminds us of what variable we analysed.

The important information is in the table that follows:

## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

## Supplement 4 357.65 89.413 5.1281 0.002331 **

## Residuals 35 610.25 17.436This is an Analysis of Variance Table. It summarises the parts of the ANOVA calculation: Df – degrees of freedom, Sum Sq – the sum of squares, Mean Sq – the mean square, F value – the F-ratio (i.e. variance ratio), Pr(>F) – the p-value.

The F-ratio (variance ratio) is the key term. This is the test statistic. It measures how large and consistent the differences between the means of the five different treatments are. Larger values indicate clearer differences between means, in just the same way that large values of Student’s t indicate clearer differences between means in the two sample situation.

The p-value gives the probability that the observed differences between the means, or a more extreme difference, could have arisen through sampling variation under the null hypothesis. What is the null hypothesis: it is one of no effect of treatment, i.e. the null hypothesis is that all the means are the same. As always, the p-value of 0.05 is used as the significance threshold, and we take p < 0.05 as evidence that at least one of the treatments is having an effect. For the corncrake data, the value is 5.1, and the probability (p) of getting an F-ratio this large is given by R as 0.0023, i.e. less than 0.05. This provides good evidence that there are differences in weight gain between at least some of the treatments.

So far so good. The test that we have just carried out is called the global test of significance. It goes by this name because it doesn’t tell us anything about which means are different. The analyses suggest that there is an effect of supplement on weight gain. Still, some uncertainty remains because we have only established that there are differences among at least some supplements. A global test doesn’t say which supplements are better or worse. This could be very important. If the significant result is generated by all supplements being equally effective (hence differing from the control but not from each other) we would draw very different conclusions than if the result was a consequence of one supplement being very effective and all the others being useless. Our result could even be produced by the supplements all being less effective than the control!

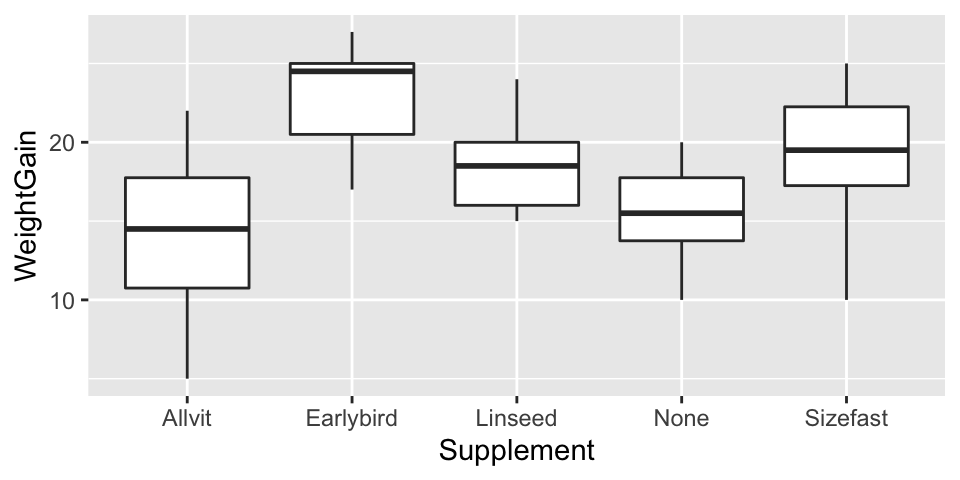

So having got a significant result in the ANOVA, we should always look at the means of the treatments to understand where the differences actually lie. We did this in the previous chapter but here is the figure again anyway:

What looking at the means tells us is that the effect of the supplements is generally to increase weight gain (with one exception, ‘Allvit’) relative to the control group (‘None’), and that it looks as though ‘Earlybird’ is the most effective, followed by ‘Sizefast’ and ‘Linseed’.

Often inspection of the means in this way will tell us all we need to know and no further work will be required. However, sometimes it is desirable to have a more rigorous way of testing where the significant differences between treatments occur. A number of tests exist as ‘add ons’ to ANOVA which enable you to do this. These are called post hoc multiple comparison tests (sometimes just ‘multiple comparison tests’). We’ll see how to conduct these later.

15.3 Presenting results

As with all tests, it will be necessary to summarise the result in a written form. With an ANOVA on several treatments, we always need to at least summarise the result of the global test of significance, for example:

There was a significant effect of supplement on the weight gain of the corncrake hatchlings (ANOVA: F=5.1; d.f.= 4,35; p<0.01).

There are several things to notice here:

The degrees of freedom are always quoted as part of the result, and…there are two values for the degrees of freedom to report in ANOVA because it involves F-ratios. These are obtained from the ANOVA table and should be given as the treatment degrees of freedom first, followed by the error degrees of freedom. Order matters. Don’t mix it up.

The degrees of freedom are important because, like a t-statistic, the significance of an F-ratio depends on the degrees of freedom, and giving them helps the reader to judge the result you are presenting. A large value may not be very significant if the sample size is small, a smaller may be highly significant if the sample sizes are large.

The F-ratio rarely needs to be quoted to more than one decimal place.

When it comes to presenting the results in a report, it helps to present the means, as the statement above cannot entirely capture the results. We could use a table to do this, but tables are ugly and difficult to interpret. A good figure is much better.

Box and whiskers plots and multi-panel dot plots or histograms are exploratory data analysis tools. We use them at the beginning of an analysis to understand the data, but we don’t tend to present them in project reports or scientific papers. Since ANOVA is designed to compare means, a minimal plot needs to show the point estimates of each group-specific mean, along with a measure of their uncertainty. We often use the standard error of the means to summarise this uncertainty.

In order to be able to plot these quantities we first have to calculate them. We can do this using dplyr. Here’s a reminder of the equation for the standard error of a mean: \[

SE = \frac{\text{Standard deviation of the sample}}{\sqrt{\text{Sample size}}} = \frac{SD}{\sqrt{n}}

\] So, the required dplyr code is:

# get the mean and the SE for each supplement

corncrake_stats <-

corn_crake %>%

group_by(Supplement) %>%

summarise(Mean = mean(WeightGain), SE = sd(WeightGain)/sqrt(n()))

# print to the console

corncrake_stats## # A tibble: 5 × 3

## Supplement Mean SE

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 Allvit 14.2 1.98

## 2 Earlybird 22.9 1.23

## 3 Linseed 18.5 1.07

## 4 None 15.6 1.21

## 5 Sizefast 19 1.69Notice that we used the n function to get the sample size. The rest of this R code should be quite familiar by now. We gave the data frame containing the group-specific means and standard errors the name corncrake_stats.

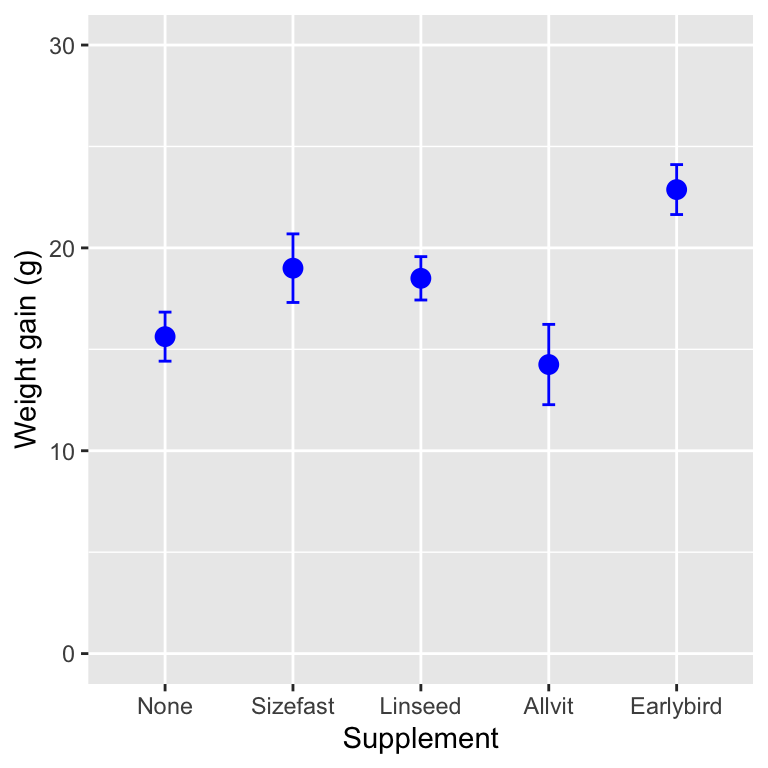

We have a couple of different options for making a good summary figure. The first plots a point for each mean and places error bars around this to show ±1 SE. In order to do this using ggplot2 we have to add two layers—the first specifies the points (the means) and the second specifies the error bar (the SE). Here is how to do this:

ggplot(data = corncrake_stats,

aes(x = Supplement, y = Mean, ymin = Mean - SE, ymax = Mean + SE)) +

# this adds the means

geom_point(colour = "blue", size = 3) +

# this adds the error bars

geom_errorbar(width = 0.1, colour = "blue") +

# controlling the appearance

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0, 30)) +

# use sensible labels

xlab("Supplement treatment") + ylab("Weight gain (g)") +

# flip x and y axes

coord_flip() +

# use a more professional theme

theme_bw()

First, notice that we set the data argument in ggplot to be the data frame containing the summary statistics (not the original raw data). Second, we set up four aesthetic mappings: x, y, ymin and ymax. Third, we added one layer using geom_point. This adds the individual points based on the x and y mappings. Fourth, we added a second layer using geom_errorbar. This adds the error bars based on the x, ymin and ymax mappings. Finally we adjusted the y limits and the labels (this last step is optional).

Factors

Now is good time to take a short detour to remind ourselves about factors. In the world of experimental design, the word ‘factor’ is used to describe a controlled variable where the levels—i.e. its different values or categories—are set by the experimenter. R includes a special type of vector for representing factors. This is called, rather sensibly, a factor. One can get quite a long way in R-land without using factors. However, we inevitably end up using them because so much of R’s plotting and statistical modelling machinery rely on factors. We are going to need to them to help us reorder the groups in our plot.

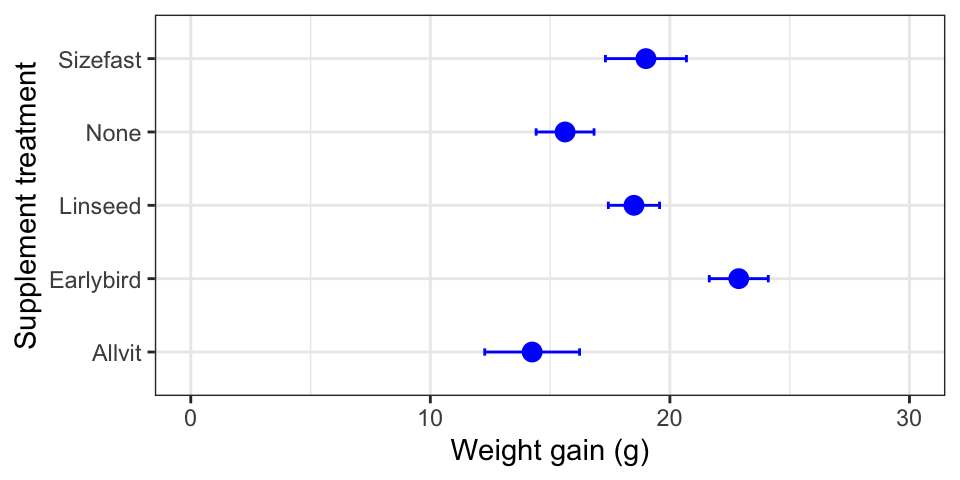

Take a close look at that last figure. Is there anything wrong with it? The control group in this study is the no diet group (‘None’). Conventionally, we display the control groups first. R hasn’t done this because the different categories of Supplement are presented in alphabetical order by default. One way to change that order if by converting Supplement to a factor and define the order we want as we do so. Here is how to do this using dplyr and a function called factor:

corncrake_stats <-

corncrake_stats %>%

mutate(Supplement = factor(Supplement,

levels = c("None", "Sizefast", "Linseed", "Allvit", "Earlybird")))We use mutate to update Supplement, using the factor function to redefine the levels of Supplement and overwrite the original. Now, when we rerun the ggplot2 code we end up with a figure like this:

The treatments are presented in the order specified with the levels argument. Problem solved!

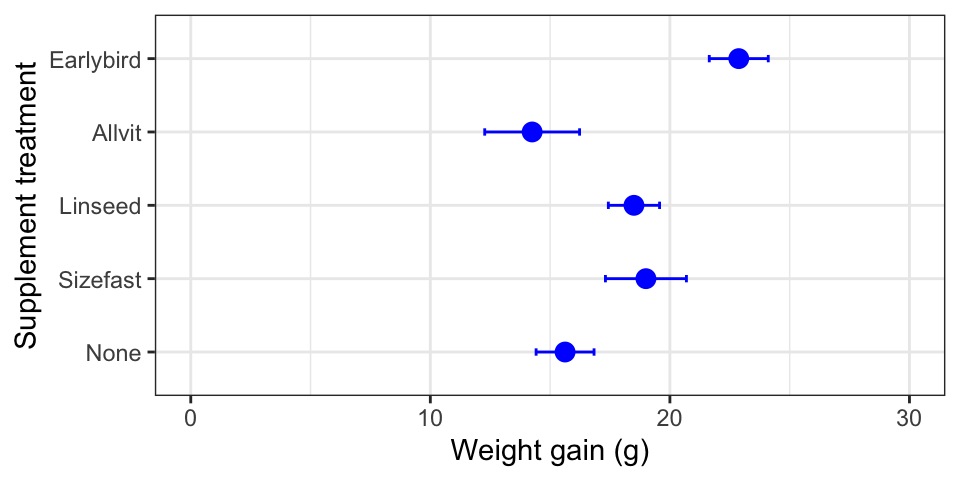

A bar plot is another popular visualisation for summarising the results of an ANOVA. We only have to change one thing about the last chunk of ggplot2 code to make a bar plot. Instead of using geom_point, we use geom_col (we’ll drop the coord_flip bit too):

ggplot(data = corncrake_stats,

aes(x = Supplement, y = Mean, ymin = Mean - SE, ymax = Mean + SE)) +

# this adds the means

geom_col(fill = "lightgrey", colour = "grey") +

# this adds the error bars

geom_errorbar(width = 0.1, colour = "black") +

# controlling the appearance

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0, 30)) +

# use sensible labels

xlab("Supplement treatment") + ylab("Weight gain (g)") +

# use a more professional theme

theme_bw()