Chapter 6 Statistical comparisons

6.1 Making comparisons

Scientific inquiry often requires us to evaluate predictions about differences between populations. The simplest such case involves just two populations, e.g.

‘Does enzyme activity differ among control and drug-treated cell lines?’

‘Do maize plants photosynthesise at different rates at 25°C and 20°C?’

‘Do purple and green plants differ in their biomass?’

In this setting, we’re evaluating whether or not two statistical populations are different in some way. To do this, we have to step through the same kind of process discussed in the last few chapters.

This chapter demonstrates how to compare two populations by employing ideas like null hypotheses and p-values. The goal is not really to learn how to compare populations—instead, we want to continue developing our understanding of significance tests and evaluate predictions.

As we do this, we’re going to introduce a new component of the frequentist machine called a ‘test statistic’. This is an important idea—it will crop up every time we introduce a new type of statistical test.

6.1.1 A new example

Let’s continue with the familiar purple and green plants example. This time, instead of working with morph frequencies, we’ll consider plant size. We introduce this by stepping through the process introduced in the learning from data chapter:

Question, hypothesis and prediction: We think the purple and green morph plants might be different in some way. Specifically, we want to address the question: Why have the purple morphs increased in frequency in the new population? Our working hypothesis is that purple plants are fitter than green plants. Since fitness is closely related to seed production, and seed production is typically positively correlated with plant size, we predict that purple morphs should be larger in the new population.

Statistical populations: What statistical populations are we interested in? This time, we will conceive of each morph as its own statistical population. That means there are now two distinct statistical populations in play: a purple plant population and a green plant population. This change of focus from our earlier analysis where we considered all the plants as one population is perfectly valid. Statistical populations are not really fixed things—they are defined by the problem we’re tackling.

Variables: Which variable should we study? An obvious way to address a prediction of size differences of plants is to measure the weight of individuals of each morph in our samples. To be more precise, ‘dry weight biomass’ is the standard, reliable measure of how ‘big’ a plant is. Dry weight mass is a numeric variable measured on a ratio scale (zero means ‘nothing’).

Population parameters: We predict that purple morphs are larger than green morphs. What do we mean by that? We probably don’t mean that every purple plant is bigger than every green plant. Instead, we need to know if purple plants are generally bigger than green ones. This is a statement about ‘central tendency’—we want to evaluate whether purple plants are larger than green plants, on average. The population parameters of interest are, therefore, the mean dry weights of each morph.

Gather samples: The next step is to gather appropriate samples. Since this is a made-up example, we’ll cut to the chase. We have already seen the samples we’re going to use. When we read in the ‘MORPH_DATA.CSV’ in the previous chapter, we found a numeric variable called Weight. This contains our dry weight biomass information. The categorical Colour variable analysed in the last chapter tells us which kind of colour morph each observation corresponds to.

Now we’re ready to tackle the remaining steps in the ‘learning from data’ process: estimating the population parameter(s), estimating uncertainty, and answering the question. We work through each of these steps in detail next.

Once again, the best way to understand what follows is by working through the example, though you can also make good progress through careful reading. In any case, the code again assumes that ‘MORPH_DATA.CSV’ has been read into a tibble called morph_data.

6.1.2 Examine the data

The first step is to calculate point estimates of the mean dry weight of each morph. These are our ‘best guess’ of the population means. It can also be useful to know something about the sample size and variability of dry weight in each sample. We can summarise variability using the standard deviation (sd) of each sample. Here is how to do this with dplyr:

# using morph data...

morph_data %>%

# ...group the data by colour morph category

group_by(Colour) %>%

# ... calculate the mean, sd and sample size of weight in each category

summarise(mean = mean(Weight),

sd = sd(Weight),

samp_size = n())## # A tibble: 2 × 4

## Colour mean sd samp_size

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <int>

## 1 Green 708. 150. 173

## 2 Purple 767. 156. 77This shows the mean dry weight of the purple morph is indeed greater than that of the green morph. Maybe our hypothesis is true. The standard deviation estimates indicate that the dry weight of purple morphs is also a bit more variable than the green morphs.

These numbers are point estimates taken from limited samples. If we sampled the populations again, sampling variation would lead to different estimates. We’re not yet in a position to conclude that purple morphs are bigger than green morphs because we don’t know if the difference is just down to ‘luck’.

We should also visualise the sample distributions of colour morph weights. We could do this in a variety of ways but since we only have two samples we may as well use a fairly information-rich summary. Histograms are a good choice when we have a reasonable amount of data:

ggplot(morph_data, aes(x = Weight)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 50) +

facet_wrap(~Colour, ncol = 1) # <- separate histogram for each colour morph!

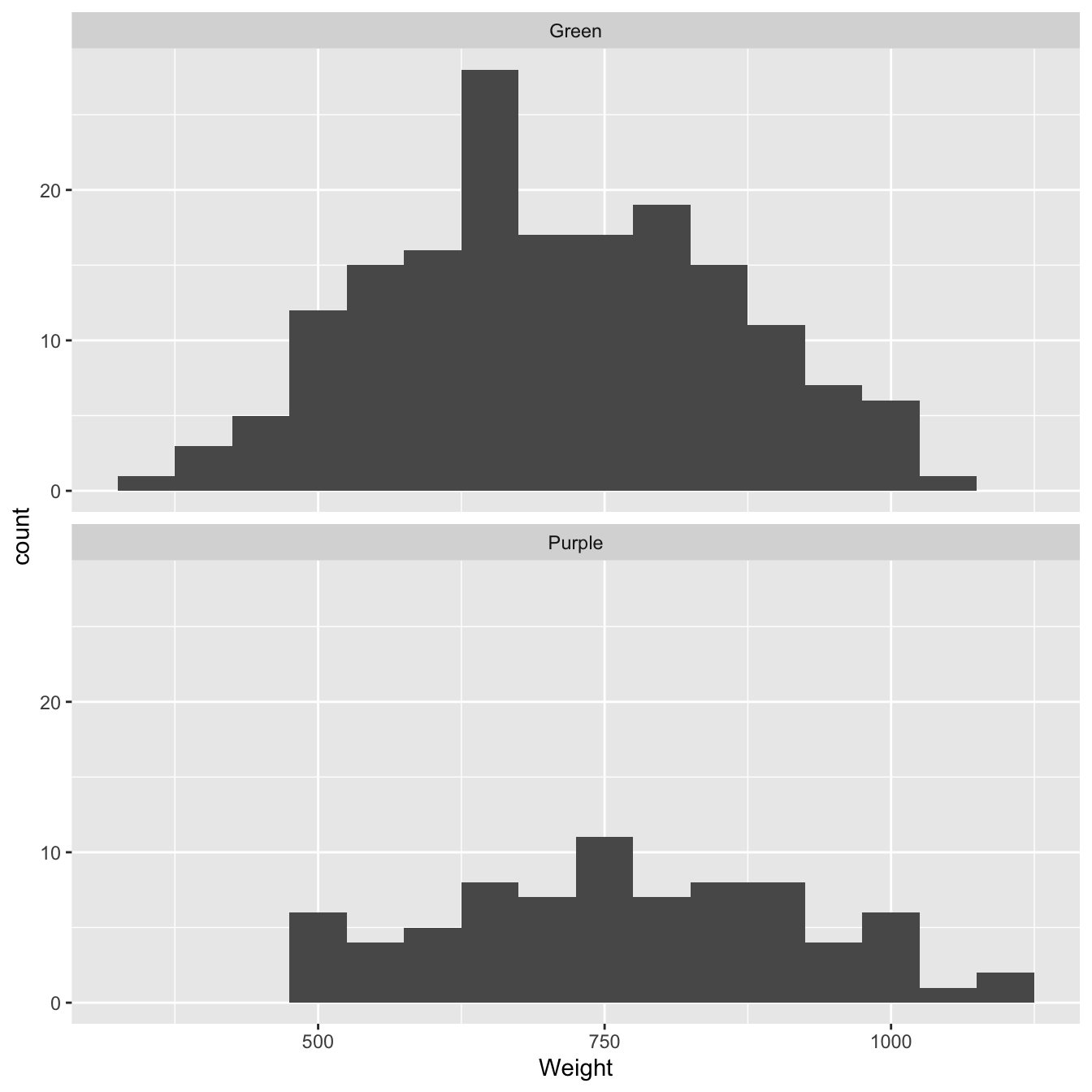

Figure 6.1: Size distributions of purple and green morph samples

What does this plot tell us? We’re interested in the degree of similarity between the two samples. It looks like purple morph individuals tend to have higher dry weights than green morphs. We already knew this, of course. What the plot confirms is that the difference is probably not due to a few extreme cases (‘outliers’).

It looks like the histograms confirm there might be a general difference in the size of the two morphs. However, there is also a lot of overlap between the two dry weight distributions. Maybe the difference between the sample means is simply a consequence of sampling variation? We need to construct a statistical test to address this question.

6.2 Constructing a test

We will develop a frequentist test to evaluate whether the two population means are likely to be different. Regardless of the precise details, this kind of problem involves a four-step process:

First, we assume there is no difference between the population means. That is, we hypothesise that all the data are sampled from a pair of populations with the same population mean. To put it another way, we pretend there is really only one population. We know about this trick. It’s a statement of the null hypothesis.

Next, we use information in the real samples to work out what would happen if we were to repeatedly take many new samples in this hypothetical situation of ‘no difference’. We summarise this by calculating the null distribution of a suitable test statistic (<– this is something new).

We then ask, “if there were no difference between the two groups, what is the probability that we would observe a difference that is the same as, or more extreme than, the one we observed in the true sample?” We know about this number too. It’s a p-value.

If the observed difference is sufficiently improbable, we conclude that we have found a statistically significant result. A statistically significant result is one that is inconsistent with the hypothesis of no difference.

This chain of logic is very similar to that used to construct the statistical test in the previous chapter. The main elaboration here is the introduction of the test statistic. When dealing with comparisons involving more than one parameter we need to work with a single numeric summary of ‘the effect of interest’, however defined. Its purpose is to summarise the effect as a single number so that we can construct a statistical test. That’s why it is called the ‘test statistic’.

There are many different kinds of test statistic and many different ways to realise the above process. We’re going to use something called a permutation test here. We’re not using this because we want to learn how to apply it. Instead, just as with the bootstrap, the permutation test offers a simple way to see how frequentist tests work without getting lost in mathematical detail.

6.2.1 Permutation tests

A hypothesis of ‘no difference’ between the mean dry weights of purple and green morphs implies the following: the labels ‘purple’ and ‘green’ are meaningless because the two morphs are effectively sampled from the same population. These labels don’t carry any real information, meaning they may as well have been randomly assigned to each individual.

This suggests we can evaluate the statistical significance of the observed difference as follows:

- Make a copy of the original purple and green dry weights sample, but do so by randomly assigning the labels ‘purple’ and ‘green’ to the new copy of the data. Do this in such a way that the original sample sizes are preserved. The process of assigning random labels is called permutation.

(We have to preserve the original sample sizes because we want to mimic the sampling process that we used, i.e. we want to hold everything constant apart from the labelling of individuals.)

Repeat the permutation scheme many times until we have a large number of artificial samples; 1000-10000 randomly permuted samples may be sufficient.

For each permuted sample, calculate whatever test statistic captures the relevant information. In our example, this is the difference between the mean dry weight of purple and green morphs in each permuted sample.

(It doesn’t matter which way round we calculate the difference.)

- Compare the observed test statistic from the real sample to the distribution of sample statistics from the randomly permuted samples.

This scheme is called a permutation test because it involves random permutation of the group labels. Why is this useful? Each unique random permutation yields an observation from the null distribution of the difference among sample means, under the assumption that this difference is zero in the population. We can use this to assess whether or not the observed difference is consistent with the hypothesis of no difference by looking at where it lies relative to this null distribution.

6.2.2 Carrying out a permutation test

It’s easy to implement a permutation test in R. We won’t show the code this time because it uses quite a few tricks that won’t be needed again. It is worth having a quick look at the permuted samples, though. The first 40 values are:

Sample 1-

## Green Purple Purple Green Green Purple Green Purple

## 714.3592 693.4924 556.2063 653.6619 672.5207 661.0097 445.1001 481.5068

## Green Green Green Green Purple Purple Green Green

## 647.6679 858.4820 567.4104 597.1629 718.7132 539.8551 753.0170 807.7700

## Purple Purple Green Green Green Green Green Green

## 1085.7036 926.4972 617.1209 632.5897 859.7013 815.4634 666.7693 573.5907

## Green Green Purple Green Purple Purple Green Green

## 694.2877 836.6883 665.8489 617.7895 590.5936 775.8980 686.6790 813.4272

## Green Green Green Purple Green Green Green Purple

## 506.3904 566.9971 629.5894 878.2477 823.1128 542.7877 507.7345 786.2809Sample 2-

## Purple Green Green Green Green Green Purple Purple

## 714.3592 693.4924 556.2063 653.6619 672.5207 661.0097 445.1001 481.5068

## Purple Green Green Purple Purple Green Purple Green

## 647.6679 858.4820 567.4104 597.1629 718.7132 539.8551 753.0170 807.7700

## Purple Green Green Green Purple Purple Green Purple

## 1085.7036 926.4972 617.1209 632.5897 859.7013 815.4634 666.7693 573.5907

## Purple Green Green Purple Green Green Green Green

## 694.2877 836.6883 665.8489 617.7895 590.5936 775.8980 686.6790 813.4272

## Purple Green Green Green Purple Green Green Purple

## 506.3904 566.9971 629.5894 878.2477 823.1128 542.7877 507.7345 786.2809The data from each permutation are stored as numeric vectors, where each element of the vector is named according to the morph type it corresponds to—these are ‘the labels’ referred to above. The set of numbers does not vary among permuted samples. The only difference between them is the labelling which has been randomly assigned in each permuted sample.

The difference between the mean dry weights in the first permutation is 4.0700017, while in the second sample, the difference is -19.9656492. What matters for our test is the distribution of these differences over the complete set of permutations. This is the approximation to the sampling distribution of the difference between means under the null hypothesis—i.e. it’s our null distribution.

We can visualise this null distribution by making a histogram that summarises the 2500 mean differences from the permuted samples:

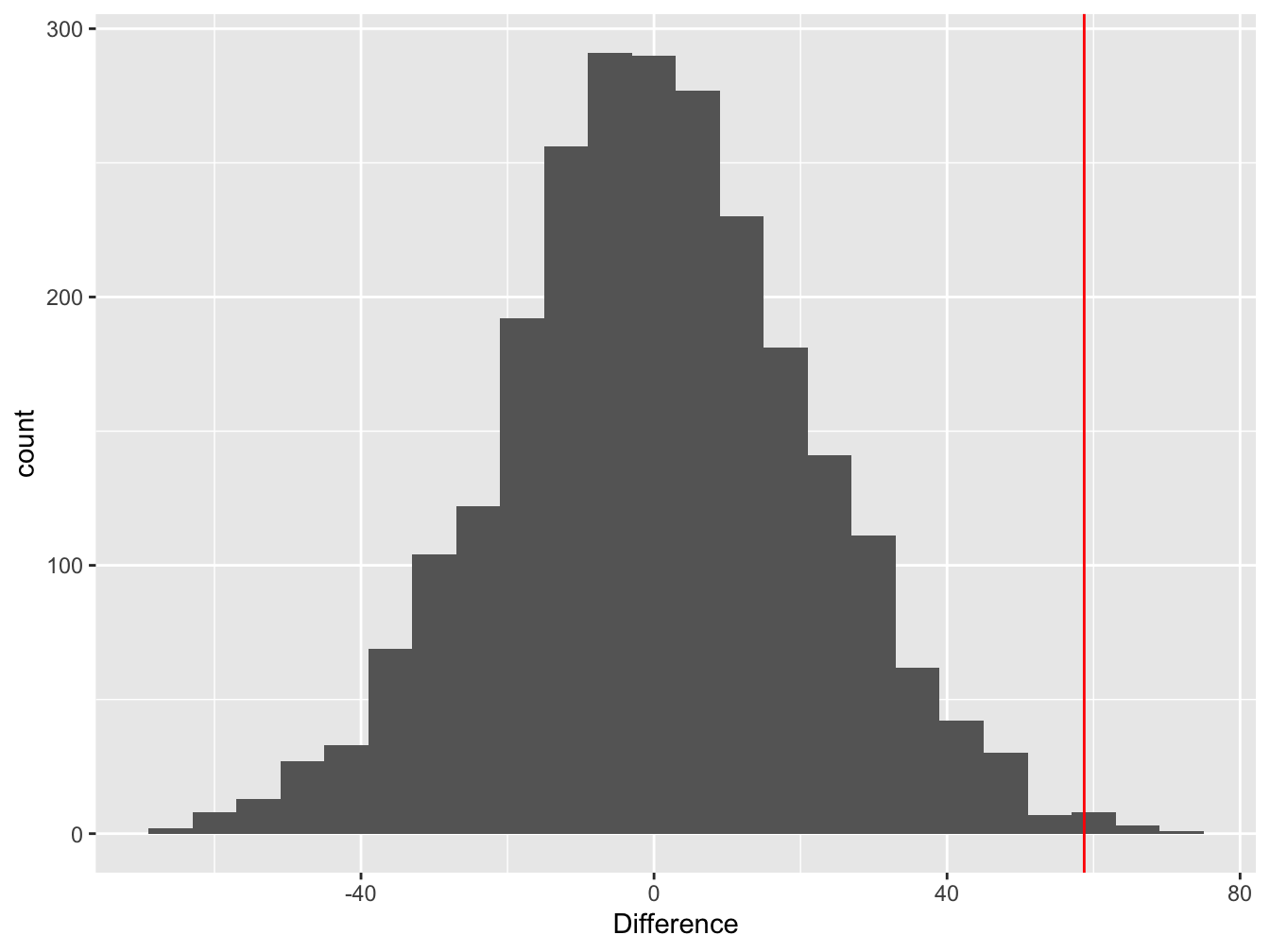

Figure 6.2: Difference between means of permuted samples

Notice that the distribution is centred at zero. This makes perfect sense—if we take a set of numbers and randomly allocate them to groups, on average, we expect the difference between the means of the groups to be zero.

The red line shows the estimated difference between the mean purple and green morph dry weights in the real sample. This is the test statistic. The key thing to notice here is the location of the test statistic within the null distribution.

In this example, the estimated difference lies at the end of the right ‘tail’ of the null distribution. What does that tell us? It suggests the observed difference (the red line) is unlikely to arise through pure sampling variation if the two population means were identical.

So… it looks like the data are inconsistent with the null hypothesis of no difference. What we need is a number to quantify this inconsistency—the all-important p-value.

Calculating the p-value

We use the null distribution to quantify the probability of ending up with the observed difference under the null hypothesis. Only 10 out of the 2500 permutations ended up being equal to, or ‘more extreme’ (more positive) than, the observed difference. This means the probability of finding a difference in the means equal to, or more positive than, the observed difference is about, p = 10/2500 = 0.004. This is the p-value for our significance test.

Let’s run through the interpretation of that p-value. Here’s the general chain of logic again… The p-value is the probability of obtaining a test statistic equal to, or ‘more extreme’ than, the estimated value, assuming the null hypothesis is true. The null hypothesis is one of no effect, so a small p-value can be interpreted as evidence for the effect (e.g. a difference between means) being present. That’s a weird way to seek evidence for the presence of an effect, but that’s how frequentist statistics works.

How low does the p-value actually have to be before we decide we have ‘enough evidence’? Less than 0.01? Less than 0.001? Any threshold is somewhat arbitrary to be honest, but in biology, a significance threshold of p < 0.05 is conventionally used. If we find p < 0.05, then we conclude that we found a ‘statistically significant’ effect at the 5% level.

Here’s how this logic applies to our example… The permutation test assumed there was no difference between the purple and green morphs, so the low p-value indicates that the estimated difference between the mean dry weight of purple and green morphs was unlikely to have occurred by chance if there is really no difference at the population level. We interpret the low p-value as evidence for the existence of a difference in mean dry weight among the populations of purple and green morphs. Since p = 0.004, we say we found a statistically significant difference at the 5% level.

Here’s how we might summarise our analysis in in a written report:

The mean dry weight biomass of purple plants (77) was significantly greater than that of green plants (173) (one-tailed permutation test, p<0.05).

We report the sample sizes used, the type of test employed, and the significance threshold we passed (not the raw p-value).

Directional tests

The test we just did is a ‘one-tailed’ test. It’s called a ‘one-tailed’ because we only looked at one end of the null distribution. This kind of test is appropriate for evaluating directional predictions (e.g. purple > green). If, instead of testing whether purple plants were larger than green plants, we just want to know if they were different in some way (i.e. in either direction), we should use a ‘two-tailed’ test. These work by looking at both ends of the null distribution. We won’t do this here though—the one- vs two-tailed distinction is discussed in the one-tailed vs. two-tailed tests supplementary chapter.

6.3 What have we learned?

Our goal was not really to learn how permutation tests work. Just as with bootstrapping in the previous chapter—we just used it to demonstrate the logic of how frequentist statistics work. In this instance, we wanted to see how to evaluate a difference between two groups. The basic ideas are no different from those introduced in the previous chapter…

define what constitutes an ‘effect’ (e.g. a difference between means), then assume that there is ‘no effect’—i.e. define the null hypothesis,

select an appropriate test statistic that can distinguish between the presence of an ‘effect’ and ‘no effect’,

(In practice, each kind of statistical test uses a standard test statistic. We don’t have to pick these ourselves.)

construct the corresponding null distribution of the test statistic by working out what would happen if we were to take frequent samples in the ‘no effect’ situation,

and finally, use the null distribution and the observed test statistic to calculate a __p-value__that quantifies how frequently the observed difference, or a more extreme difference, would be observed under the hypothesis of no effect.

We only actually introduced one new idea in this chapter. When evaluating differences among populations, we need to work with a single number that can distinguish between ‘effect’ and ‘no effect’. This is called the test statistic. Sometimes this can be expressed in terms of familiar quantities like means (we just used a difference between means above). However, this isn’t always the case. For example, we can use something called an F-ratio to evaluate the statistical significance of differences among more than two means. We’ll get to these kinds of tests later. For now, our task is to explore simple ‘parametric tests’. These kinds of tests allow us to ask questions without resorting to things bootstrapping or permutation tests.